<p><br>

<strong>New America Media</strong></p>

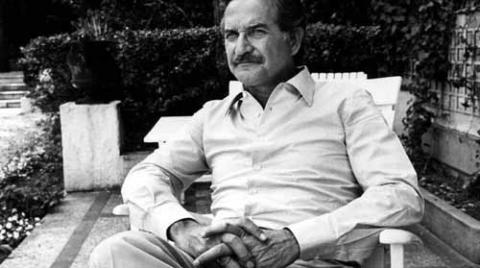

<p><strong><a class="highslide" onclick="return vz.expand(this)" href="https://cms.laprensa.org/sites/default/files/2012/05/nevaer_fuentes500x… loading="lazy" class="alignright size-medium wp-image-17703" title="nevaer_fuentes500x279" src="https://cms.laprensa.org/sites/default/files/2012/05/nevaer_fuentes500x…; alt="" width="300" height="167" srcset="https://cms.laprensa.org/sites/default/files/2012/05/nevaer_fuentes500x… 300w, https://cms.laprensa.org/sites/default/files/2012/05/nevaer_fuentes500x… 500w" sizes="(max-width: 300px) 100vw, 300px"></a>MERIDA, Mex.</strong> – The sudden death of Carlos Fuentes, Mexican novelist, social critic and man of letters, last week at the age of 83, has cast a shadow over the nation just weeks before voters here will go to the polls to elect new leaders, including the president, in national elections.</p>

<p>Newspapers around the world, from the New York Times to Spain’s El País, to France’s Le Monde and Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald, have published obituaries and tributes detailing the body of Fuentes’ work as a writer and an intellectual, yet few have adequately conveyed the degree to which his work impacted the country politically.</p>

<p>Often overlooked is the fact that Carlos Fuentes played a key role in Mexico’s transition from a one-party state to a democratic one. Perhaps more than any other single Mexican, Fuentes worked to lay the intellectual foundation for Mexico becoming a functioning democracy.</p>

<p>Fuentes was a catalyst in the 1960s, along with Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortazar and Mario Vargas Llosa, of the literary movement known as “El Boom,” which brought Latin American literature to the international forefront. He was also one of Mexico’s great public intellectuals, delighting in political engagement and dialogue that helped the nation re-imagine what it could ultimately become.</p>

<p>After the success of his 1959 novel, “The Good Conscience” – it tells the story of a bourgeois young man who rationalizes the hypocrisy necessary to live a life of privilege in a flawed society — Fuentes began to publicly question Mexico’s economic development model. Adopted after World War II with the blessing of the United States, the model promised political stability via a one-party system flexible enough to accommodate the competing demands of Mexican society.</p>

<p>That doctrine essentially cemented political power for the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), and established an economic system that opened the door for the eventual economic domination of Mexico by U.S. corporations.</p>

<p>Such a model may have seemed appropriate enough for a nation that was, in the mid-twentieth century, mainly agrarian with a population lacking the educational wherewithal to aspire to much more, and with a middle class still in the early stages of development.</p>

<p>It was in this context that Octavio Paz, in 1950, wrote his essay on the nature of the Mexican character, “The Labyrinth of Solitude.” Paz soon emerged as the leading public intellectual in favor of a one-party political system characterized by a closed economy. The Mexican government subsequently lavished Paz with money to support his intellectual aspirations, funding colloquiums, academic magazines, art exhibitions and any other means necessary to authenticate the government’s Orwellian approach to social, economic and political engineering.</p>

<p>For a quarter century, the development model worked. But what was appropriate in an agrarian economy eventually came to be outdated, as Mexico industrialized and the country’s urban population swelled.</p>

<p>The friendship and collaboration between Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes flourished in the 1960s and 70s. Both men enjoyed the blessing of the Mexican state, Paz being appointed Mexico’s ambassador to India, and Fuentes as ambassador to France. A common debate heard among Mexicans in those years was which author would be awarded the Nobel Prize in literature first. (Paz won the Nobel Prize in 1990 for his “impassioned writing with wide horizons, characterized by sensuous intelligence and humanistic integrity.”)</p>

<p>Although he’d recognized the problems inherent in Mexico’s system years earlier, it wasn’t until the 1980s that Fuentes, who had taught abroad at various universities in the United States and Europe, fully came to acknowledge the limitations of Mexico’s economic model and one-party system.</p>

<p>What were the aspirations of Mexico’s middle class? Had the limits of an import-substitution economic model been reached? How long could the PRI – which governed longer than the Communist Party in the Soviet Union – continue to dominate the nation’s political life?</p>

<p>Fuentes began to embrace and even champion the notion that the PRI should lose a few elections every now and then. With age, he became more liberal and left-leaning in his politics, and spoke in support of political movements that, in his own mind, were willing to experiment with innovative development models. Paz, on the other hand, did not.</p>

<p>When Fuentes publicly defended the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, it created a rift between him and Paz. The latter, considered the leading intellectual voice of the Mexican State, could not endorse a revolution that could very well challenge Mexico’s own political system. From there, the personal relationship between the two went downhill, even resulting in public spats and squabbles.</p>

<p>In 1988, Vuelta, a literary magazine edited by Paz, criticized Fuentes. That Fuentes’ novel, “The Old Gringo,” published three years before, had become a bestseller in the United States was both an irritation to Paz and a source of jealousy. Some Mexicans turned away from Fuentes, with some even challenging his “Mexicanness,” by virtue of his having been born in Panama. (His father was a Mexican diplomat assigned to Panama at the time.) Others suggested he should move to Los Angeles to be closer to Jane Fonda (who starred, along with Gregory Peck, in the film adaptation of “The Old Gringo.”)</p>

<p>It was a dark period in his career. “Christopher Unborn,” published in 1987, is arguably the worst of his novels. Fuentes acknowledged as much when I pointed this out to him, describing that novel as a crime against forestry. “Fortunately it did not sell well,” he said, “so not that many trees were cut in vain.”</p>

<p>Fuentes remained adamant in pressing for an “opening” of the Mexican economic system. Meanwhile, his criticisms of the Mexican model were being laid bare by another intellectual, Mario Vargas Llosa, who during a live broadcast interview conducted by Octavio Paz in 1990 called Mexico “a perfect dictatorship.” The studio fell silent, Octavio Paz stammered and the station abruptly cut to commercials.</p>

<p>Vargas Llosa later said that what he meant was that Mexico’s dictatorship of the PRI, by the PRI and for the PRI was perfect, insofar as the Mexicans were too stupid to realize they were living under a dictatorship.</p>

<p>Paz never recovered, and his Nobel Prize in Literature was seen as more mocking than honorable. He would die in 1998. Neither Fuentes nor Paz ever reconciled or apologized to one another.</p>

<p>In the intervening time, the Mexican nation was changing. The economy demanded greater integration with the world economy, and this culminated in 1994 with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).</p>

<p>Throughout the 1990s, Fuentes championed the ideals of democracy, transparency in government and a more equitable distribution of the nation’s resources. Mexico’s democratic institutions strengthened, and Fuentes found an ally in President Ernesto Zedillo, counseling the president to not “fear” the democratic choices of the Mexican people. The triumph of his vision was evident in July 2000 when Zedillo addressed the nation to announce that the winner of the presidential election and the next president of Mexico would be Vicente Fox, from the opposition National Action Party (PAN).</p>

<p>Democracy had triumphed, and so had Fuentes’ intellectual vision for Mexico.</p>

<p>In the same manner that Paz was the intellectual who provided gravitas to the one-party system that dominated the second half of the twentieth century in Mexico, Fuentes was the intellectual midwife to Mexican democracy.</p>

<p>Fuentes had emerged, after Paz’s death and in the later stages of his life, as Mexico’s elder statesman of letters. Yet he spent his final years in a state of melancholy over the untimely death of his only son in 1999. How does one transcend the ghost of a 26-year old who died before his prime? In his last essay, published by the newspaper Reforma just one day before his death, he laments that the presidential candidates in July’s elections have no answer for the challenges facing Mexico.</p>

<p>Even as Mexico mourns Carlos Fuentes, it is left to commence the search for an intellectual voice that can match his own, something this post-globalization, middle-class nation that so desperately wants peace, needs now more than ever.</p>

Image

Image

Category