How a Mexican artist’s seven-month visit to Los Angeles became a cultural touchstone

By Tessie Borden

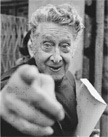

The painter David Alfaro Siqueiros is world-famous but little-known to audiences in the United States and in Los Angeles. Even so, the Mexican muralist has had an intimate, if little-known, connection to the city since the day in 1932 that he arrived for a short stay.

Call it a love-hate relationship.

That connection was the subject of América Tropical at Last, a June 18 artist panel discussion at the Mexican Cultural Institute at Olvera Street. Among the speakers were artists John Valadez and Judy Baca, as well as Luis C. Garza, curator of the Autry’s upcoming “Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied” exhibition. They spoke to an audience of about 140.

“The Mexican school of art influenced FDR to do the WPA program,” Valadez said. “He got the idea directly from the Mexican school of art.”

When he arrived in Los Angeles, Siqueiros was trying to stay a step ahead of the government for which he’d fought during the Mexican Revolution fifteen years earlier. As it became mired in factional struggles and repressive actions, Siqueiros became increasingly disillusioned, openly voicing his critiques and paying for them with prison time and self-imposed exile.

And then, he arrived in Los Angeles for what turned out to be a short stint in the United States. Nevertheless, Siqueiros was a whirlwind, painting three murals, including one that left a controversial mark on one of Los Angeles’ oldest and most historic streets.

In the minds of those who commissioned Siqueiros to paint it for the side of the Italian Hall on picturesque Olvera Street in El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, América Tropical was to be a placid landscape of bucolic life in Latin America.

Siqueiros instead painted a scene of unspeakable violence: an indigenous man tied to a double cross and left to die, with an American eagle above his head and imperialist/industrialist forces closing in. The mural caused a sensation and led eventually to the revocation of the travel visa that allowed Siqueiros to be in the United States. He left soon after.

Less than two years later, América Tropical had been partially whitewashed and allowed to fall into disrepair, fading in the Southern California sun. In another decade, it had been completely covered over. And yet, the mural remained lodged in the psyche of the city, and try as they might, civic leaders were never able to completely erase it.

Artists who knew about the mural took it as inspiration, and those who studied Siqueiros’ work emulated his techniques. The Chicano Muralist Movement of the 1960s and 1970s took some of its political and aesthetic cues from Siqueiros’ work.

Eventually, some who still remembered the mural came together to try to restore it, stabilize it and preserve it. In 1988, the Getty Conservation Institute began an ongoing conservation project to save the mural, which continues today.

During the discussion, each of the artists talked about a different aspect of Siqueiros’ art and its influence, from the pre-Columbian symbols it employed to the role it played in their own personal projects.

Baca, for example, spoke about how places that have witnessed violence become repositories of its memory. That has been part of what influenced her to embark on her decades-long Great Wall project along the Los Angeles river.

“There is a kind of energy that is in Place,” Baca said. “When I was a child, we used to go through the fields and there would be hot and cold places there and we talked about the things that occurred there. You could feel the energy of a particular place.”

That same idea propelled Siqueiros to try to move his art into the public sphere, to show it in the open air and to give it the energy of the masses and the workers passing by. And that concept also propelled the Chicano artists who worked with city and other government entities to make public murals throughout Los Angeles.

“At a time in the 1970s when we began this movement, murals were the central entrance for people of color to speak,” Baca said. “Thereafter, they became the voices of communities. They are critical as sites of public memory.”

Baca pleaded for the safety of the 1,500 murals that adorn public places in Los Angeles, many of which she said are being neglected, allowed to be covered over, and their city permits allowed to lapse.

“The disappearance of the murals is the same kind of neglect and censorship” as what happened to Siqueiros all those years ago, she said.

“Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied” opens at the Autry on Sept. 24.

http://blog.theautry.org/2010/06/29/david-alfaro-siqueiros-and-los-angeles-an-indelible-connection/