By Sally Salazar

Editor’s note: A Wikipedia entry describes Ruben Salazar as:… a Mexican-American journalist killed by a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputy during the National Chicano Moratorium March against the Vietnam War on August 29, 1970 in East Los Angeles, California. During the 1970s, his killing was often cited as a symbol of unjust treatment of Chicanos by law enforcement. Working as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, Salazar was the first Mexican-American journalist from mainstream media to cover the Chicano community.

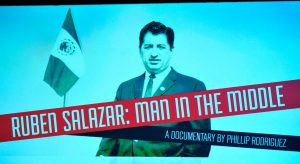

In honor of his trailblazing journalism and controversial death, a documentary titled Rubén Salazar: Man in the Middle debuts in April. The following piece was penned by Salazar’s wife, Sally, who wrote this column for Hispanic Link on the tenth anniversary of her husband’s death in 1980.

Everyone knew that the day would be one of extreme tension. Emotions were building about U.S. involvement in the war in Southeast Asia. These were placed on top of growing antagonism in the Mexican American community against the educational system and the police.

The parade in East Los Angeles that final Saturday in August 10 years ago was a Chicano expression of protest against the war. The “moratorium march” of Aug. 29, 1970, was staged more than 30 miles from our suburban OrangeCounty home in Santa Ana.

The parade in East Los Angeles that final Saturday in August 10 years ago was a Chicano expression of protest against the war. The “moratorium march” of Aug. 29, 1970, was staged more than 30 miles from our suburban OrangeCounty home in Santa Ana.

At the time, my husband Rubén was news director of KMEX, Los Angeles’ Spanish-language TV station. He had assigned a crew to cover the event. He didn’t have to go. He didn’t really want to. He dragged his feet all morning. I probably could have talked him into staying home.

Rubén had changed in those last few weeks. Whenever he left the house, he made a special point of telling me exactly where he was going to be – something he’d never done before. He started coming home straight from work every evening.

That week he had taken all the pictures off his walls at the office. He cleaned out his wallet.

When a reporter who worked with him at KMEX borrowed some other pictures — pictures Rubén had brought back from Vietnam — Rubén tossed him his book of news-contact phone numbers. Rubén told him: “I’ll get it from you Monday. If I don’t come back, it’s yours.”

Only days before that, an old Associated Press friend was over for dinner and Rubén was talking about his job and his new involvement in the Mexican-American community.

“Everything’s going so well for me,” I remember Rubén saying. “Something has to go wrong. Something has to happen.”

“You know,” he added, “they need a martyr.”

For whatever reasons newspeople have for doing those things, Rubén went to the parade that Saturday.

It’s history that he never came home.

Rubén was killed by a police tear-gas projectile. I lost my husband. Our three children — Lisa, Stephanie and Johnny, only 9, 8 and 5 years old then — lost their father.

Ten years later, my memories are confused by the murals and memorials and a creation built in the public mind — someone other people call Rubén Salazar, but someone who to this day I don’t fully recognize.

I don’t claim we were the only ones who knew Rubén. But we knew him very well. He was as a father and husband should be. There’s an age children reach when their fathers share more of their selves with them. Our children had reached that age and Rubén had responded.

He loved them and he loved his blond Anglo wife — me.

The Rubén Salazar who became a cause for a million young activist Chicanos and a symbol to millions more around the country was someone he himself may have just been in the process of discovering.

The Rubén I knew had left the barrio behind, in El Paso, Texas, many, many years before. In a Newsweek interview published just before his death, he described himself as “middle-class establishment.” His favorite meal was steak and corn. He liked Louis Roth suits. Our circle of friends were newspaper people, and Rubén loved nothing more than to engage them in lengthy debates on issues of the day. The intriguing part of him was that he could and would take either side of an argument.

Rubén was 42 when he was killed. In his 10 years with the Los Angeles Times, he covered every kind of story. The day after Mother’s Day in 1965, he was sent to Santo Domingo to report on the Dominican revolution. Then he went to Vietnam. That pleased him. He felt the paper finally viewed him as a whole reporter, not just a Mexican reporter.

“At least I didn’t get the assignment because I speak Spanish,” he told me.

After that, we spent three years in Mexico City, where he was the Times’ bureau chief, before coming back to California in 1969. Whenever he was in Los Angeles, the paper assigned him to cover the Mexican-American community.

In April of 1970, he went to KMEX, but was asked by the Times to contribute a weekly column on Mexican-American affairs.

“The Times ended up getting much more than it had bargained for,” the Newsweek article commented. It’s possible that what happened in the next few months set off some chain reactions that changed the man and created the myth. What occurred certainly played on his sense of decency and fairness, qualities always prominent in Rubén.

Born in Juárez, just below the El Paso border, Rubén enjoyed his role as an interpreter of culture and people. He did as long as there was no inference that he couldn’t compete with his Anglo peers as an equal.

His pride in his Mexican heritage was absolute, but his tastes and ambitions blended into another world where he chose to compete. He apologized to neither community for being a man in the middle.

I sometimes sensed he felt a little guilty about leading such an “Anglo” existence, but he still took peculiar delight in my accompanying him to functions put on by the militants of that era.

“You’re going to shake up the Mexicans tonight,” he’d tease me.

But a different Rubén may have been taking shape in these final weeks. More than anything else, police treatment of, and attitudes about, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans caused it to emerge.

Rubén assigned KMEX crews to cover the story in great detail when the Los Angeles police, searching for a fugitive murderer, mistakenly killed some frightened undocumented workers.

The police department went to Rubén’s boss at KMEX, Danny Villanueva. They said the Mexican community in Los Angeles wasn’t sophisticated enough to hear or read such stories. They challenged Rubén’s objectivity — in effect, his professional honesty.

That was the wrong thing to do. When Rubén knew he was right, no one could intimidate or frighten him. What the community saw was someone who could stand up to the Anglo power structure. He couldn’t back down because he knew he was right in what he did.

The power of his own words enveloped him very quickly. It caused him to tumble down from his ivory tower, to roll off the rubber raft in our backyard swimming pool, where he found life so enjoyable.

Since Rubén’s death, strangers have told me so many things about my husband. They tell me how they used to watch him deliver the news every night. Actually, as news director, he never appeared on camera. They tell me how eloquent he was in Spanish. Again, he never appeared as a commentator. His language of communication was English.

So many people have told me, “I didn’t know your husband well, but I had a drink with him once…”

If he drank all the drinks people say they drank with him, he would never have had time to write a word, let alone find his way home. With our children growing up, he liked to be home for dinner, and it bothered him that the news show kept him at the studio till 8:30 every night.

Not long ago, I took one of our daughters to a banquet where Rubén was eulogized as a great and formidable barrio leader.

When the speakers finished, my daughter turned to me and said, “Mother, that’s not my father they’re talking about.”

I should be flattered that barrio murals place Rubén alongside Benito Juárez and César Chávez. I should be flattered that so many strangers attribute so many exploits to him. In many ways, I am. But the Rubén they describe isn’t the Rubén I knew.

It’s not the Rubén Salazar who lived in our house. It’s not the gentle, humorous Rubén my children and I counted on and loved.

Had more time been given to him, he might have become the other person. He had an ability to live up to and surpass others’ expectations of him.

But that’s something we’ll never know.