As the Drug War Intensifies, Will the Free Press Be Silenced?

Credit: Claudio Rocha/Quiet Pict

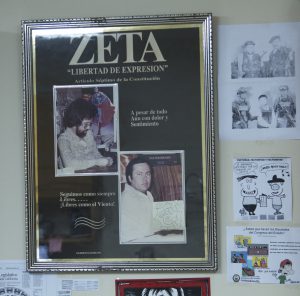

In 1980, Jesús Blancornelas and Héctor Félix Miranda founded the Mexican newsweekly Zeta. They intended it to stand as an independent voice, different from the rest of the nation’s largely government-controlled media. At the time, reporting the truth about the country’s leaders was unprecedented—and risky. To secure the fledgling Tijuana paper’s survival, Blancornelas and Miranda located its printing operation across the border in California. The paper’s uncompromising stand against corruption (which included poking fun at those who practiced it) would bring it 30,000 readers—and anger from the country’s leadership.

Though Blancornelas was aware that they were making enemies, Miranda’s 1988 murder shocked him and the rest of the country. And the dangers Zeta’s staff would face were only beginning. Committed to investigative journalism, the muckraking weekly began reporting on Mexico’s deadly drug cartels and the public officials secretly working for them. The Zeta staff’s brave stance—and that of like-minded journalists throughout Mexico—has since cost dozens of lives, making the neighbor to the south of the United States one of the world’s most dangerous nations for reporters. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that 48 journalists were murdered or disappeared during the portion of Felipe Calderón’s tenure as president from December 2006 to the close of 2011.

Bernardo Ruiz’s “Reportero” tells the heroic and troubling story of Zeta by following veteran reporter Sergio Haro and his colleagues. The film will premiere on PBS as a special broadcast of POV (Point of View) on Monday, Jan. 7, 2013 at 10 p.m. (Check local listings.) The film will stream on POV’s website, www.pbs.org/pov/reportero, from Jan. 8 – Feb. 7, 2013.

In 1980, the Mexican media didn’t look favorably upon reporters like Jesús Blancornelas who challenged the party line. After being fired by five newspapers, Blancornelas took matters into his own hands, founding Zeta and initially managing it from the United States. The paper, owned by journalists, attracted other talented journalists, including Sergio Haro, who first joined as a photographer in 1987.

Héctor Félix Miranda, Zeta’s co-founder, became one of its most popular columnists, writing humorously about the foibles of Mexico’s politicians and social elite, using tips from readers happy to see these once-untouchable figures brought down to earth. “My work in Zeta is proof that freedom of expression exists in Mexico,” said Miranda. “That others don’t practice it is their own fault.” It was assumed there would be some pushback, but what happened was horrific and unexpected: On April 20, 1988, Miranda was shot dead by thugs who worked for Jorge Hank, son of one of Mexico’s most powerful families. Hank was never investigated and would later be elected mayor of Tijuana.

Gradually, the government’s hold over the media loosened. But Zeta was developing a far more deadly enemy. By the early 1990s, drug trafficking was becoming a major industry along Mexico’s border with the United States. Cartels generated huge sums of money and used it to fund lavish lifestyles, recruit a revolving network of dealers and pay off police and government officials. The drug gangs’ violent rule enveloped the entire border region. “As journalists, we couldn’t ignore this real problem,” says Zeta co-director Adela Navarro, “so Zeta began to investigate narco-trafficking.”

Taking a stand against the traffickers had its price. In 1997, Blancornelas was ambushed by 10 gunmen working for a cartel that had moved from Sinaloa to Tijuana to traffic shipments of cocaine into the United States. Blancornelas survived only because, in a moment of poetic justice, shrapnel from one of the gunmen’s bullets ricocheted and struck the gang’s lead assassin in the eye, killing him.

In 1997, Haro left Zeta to found another independent newspaper, Siete Días, with Benjamín Flores. Flores was an ambitious reporter, and the paper took an aggressive stance against local drug lords. “Benjamín was very young, but grounded,” says Haro. “Daring and audacious. But given the kind of reporting he was doing, I thought Benjamín didn’t understand what he was getting into.” Flores was murdered just days after his 29th birthday; his killer was apprehended but set free by Mexico’s judiciary.

Haro retaliated through the press. “We mocked [the kil-ler’s] release, with photos of all the kilos he was trafficking,” he recalls. A couple of days later, Haro’s own life was threatened. Guards were appointed to protect him, while at Zeta, Blancornelas employed more than 20 bodyguards. In a testament to how bad things have gotten in Mexico, Reportero features a spokesman from a car armoring service that offers customers varying levels of protection. “Level four can withstand an AK-47, and level five can withstand armor-piercing AR-15s,” he says impassively. “If you want to protect yourself or your family from threat of kidnapping, we recommend level four, four-plus or five. Six or seven are for someone who . . . feels someone wants to kill him.”

Blancornelas decided that Zeta’s most explosive reporting should no longer carry a byline, but reporter Francisco Ortiz insisted on keeping his in a report—complete with names and photos—on organized crime figures who had received fake IDs from the attorney general’s office. Ortiz was gunned down in 2005, moments after he buckled his two children into the back seat of his car. Going forward, articles with sensitive information would carry a collective byline reading simply, “Investigation by Zeta.”

On Nov. 23, 2006, Blancornelas, indomitable founder of Zeta, passed away not from a bullet, but from stomach cancer, and Navarro took the reins. To this day, beginning every Thursday evening, the 92-page weekly is printed just outside of San Diego and trucked to Tijuana.

In 2012, Zeta marked its 32nd year of publishing truth to very deadly power. “Only the gunmen who killed Héctor Félix were arrested,” says Navarro. “The mastermind is still on the loose. The case of Blancornelas’ attack remains unsolved. The crime against Francisco Ortiz in 2004 also remains unsolved. . . . The criminals have impunity. Impunity to kill whomever they want.” But Zeta continues.

And after 25 years of reporting, the deaths of three of his colleagues and threats against his own life, Haro knows he has every reason to walk away. “It’s easier to look the other way and not cover this issue,” he says in Reportero. “But in the end you would become another accomplice. For the rest of my life, I only want to be a reporter.” He writes every week, telling the stories of the residents of northern Mexico during this wave of unprecedented violence.

The story of Zeta and its editorial team came to Mexican-born filmmaker Bernardo Ruiz accidentally. Planning a film on deported children in Mexicali, he scheduled a short meeting with Haro. It turned into a three-hour conversation. “From that first meeting forward, I understood that all of the narrative threads I had been chasing—immigration, corruption and the rise of narco power in Mexico—converged in Sergio’s story,” says Ruiz.

He developed Reportero over the course of three years, meeting with Haro on dozens of occasions. “What goes through a reporter’s mind when he or she is about to break a story that is, as Sergio says in the film, ‘like a grenade before you remove the pin’?” asks Ruiz. “Why persist when the risks are many, the benefits few? Reportero poses the same question that serves as the title of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya’s final dispatches before she was murdered in 2006: Is journalism worth dying for?

“For me, Reportero is an act of remembrance. It is a wake for Sergio’s colleagues, who have paid for their work with their blood. The film is an act of celebration, for Sergio Haro and his many colleagues, who stubbornly persist.”

At least 60,000 people have died of drug-related violence during Calderón’s six-year presidency. Many put that number much higher (Mexican newsweekly Proceso published a death count above 88,000). Enrique Peña Nieto was inaugurated as Mexico’s new president on Dec. 1, 2012, amid protests against the return to power of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Peña Nieto promises to reduce drug-related violence. In June 2012, after four Mexican newsrooms were targeted, the Mexican Congress passed a constitutional amendment giving the federal government jurisdiction over journalist murders, which previously were prosecuted by local authorities. The CPJ and others argue that this measure is inadequate until the government outlines its responsibilities and allocates federal resources.